by Alexis Devenin, PMP

In engineering projects, not all the requirements are based in scientific or technical knowledge. Much of the technical constraints are just beliefs or opinions. An engineering manager could limit his task to recollect technical requirements, accepting all of them and then design a solution that satisfies all technical constraints. Nevertheless, the additional “false constraints” usually enforce to design complicated and over-sophisticated solutions, expensive and difficult to implement.

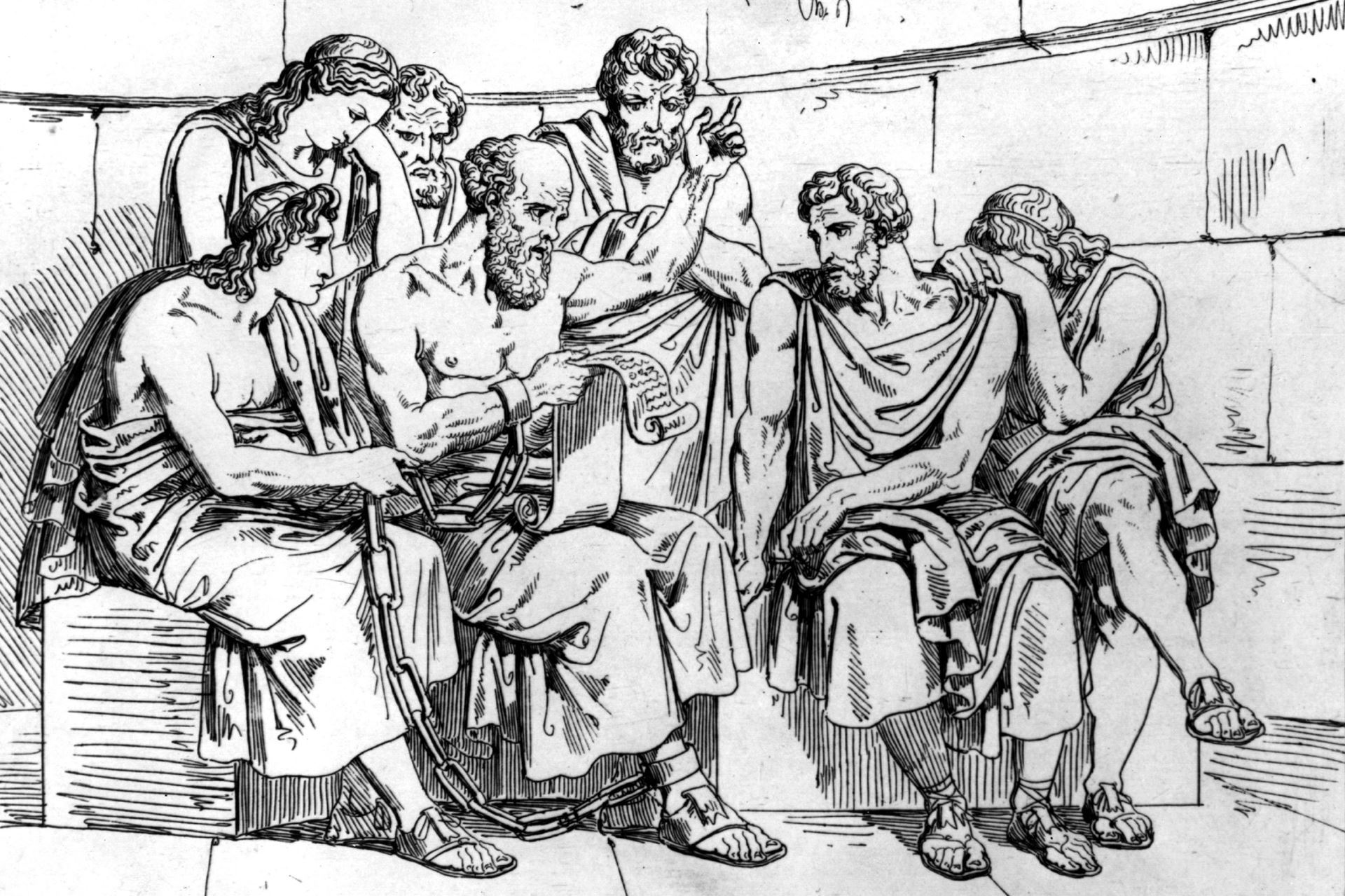

Ancient Greek philosophers identify several levels of knowledge. Doxa means belief or opinion. Episteme in contrast, means real knowledge, based on reasoning and scientific thinking. During the technical requirements elicitation of an engineering project, usually there are many doxa requirements, constraints or boundary conditions based on opinions instead of engineering analysis. It is important to investigate the validity of these constraints in order to arrive at simple and robust solutions for the system to be designed and to avoid complicated and dysfunctional designs.

Then the question is: How do you identify the 'doxa' requirements, disclose their nature, and convince the stakeholders?

The philosopher Socrates used to say that he did not have any specific knowledge, as he declares in his famous phrase, “I only know that I know nothing.” However, he believed to possess the ability to give birth to the truth, dialoguing with those who did have knowledge. He calls his method of inquiry maieutic. He said that he inherited this skill from his mother who was a midwife. Through inquiry, he was able to bring a person’s latent ideas into explicit insights. The “5 Whys” widely used in quality management could be considered a very simplistic version of the Socratic method.

The Socratic method of inquiry applied to engineering management demands certain soft skills. To question stakeholders or experts’ requirements can produce defensive responses. In the case of Socrates, his dialogues were done in public sites in Athens, under the watchful eye of the public. Once it becomes obvious that the supposed “expert” has no real knowledge about the topic, ego and prestige of the expert become damaged. Over time, this generated hatred towards Socrates, and finally he was accused of false crimes and condemned to death.

Socrates’ maieutic gives us an important insight: the engineering manager or the system engineer, is not necessarily the expert in the technology related to the system under design. However, they must be a person who has the skill to meet the experts, and through a methodic and disciplined approach, to arrive at appropriate technical solutions via the experts’ “know-how”.

About the Author

Alexis Devenin is a Mechanical Engineer with his MBA and PMP certification. He is an Engineering Project Manager with 20 years of experience in the Steel, Mining and Renewable Energy industries. Connect with Alexis on LinkedIn.

Alexis Devenin is a Mechanical Engineer with his MBA and PMP certification. He is an Engineering Project Manager with 20 years of experience in the Steel, Mining and Renewable Energy industries. Connect with Alexis on LinkedIn.